-

Title

-

Boletin Eclesiastico de Filipinas

-

Description

-

Boletin Eclesiastico de Filipinas Official Interdiocesan Organ is published monthly by the University of Santo Tomas and is printed at U.S.T. Press, Manila, Philippines.

-

Issue Date

-

Volume XLIV (Issue No. 494) July 1970

-

Publisher

-

University of Santo Tomas

-

Language

-

English

-

Subject

-

Catholic Church--Philippines--Periodicals.

-

Philippines -- Religion -- Periodicals.

-

Rights

-

-

Place of publication

-

Manila

-

extracted text

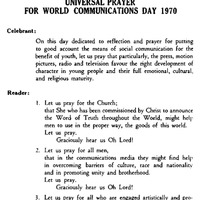

-