-

Title

-

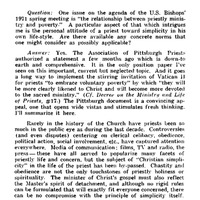

Boletin Eclesiastico de Filipinas

-

Description

-

An official Interdiocesan organ published bi-monthly by the University of Santo Tomas and printed at U.S.T. Press Manila Philippines.

-

Issue Date

-

Volume XLV (Issue No. 506) August 1971

-

Publisher

-

University of Santo Tomas

-

Year

-

1971

-

Language

-

English

-

Spanish

-

Subject

-

Catholic Church--Philippines--Periodicals

-

Philippines -- Religion -- Periodicals.

-

Rights

-

-

Place of publication

-

Manila

-

extracted text

-